Are Enduring Lessons Emerging from Online Learning?

Lockdown 3 is well underway. There is confirmation of extension until at least March, and dark suspicions that it might last until Easter. Winter weather and early darkness. Final hopes for inter-school sport, and national competition, have evaporated. It appears a bleak time for sport in schools.

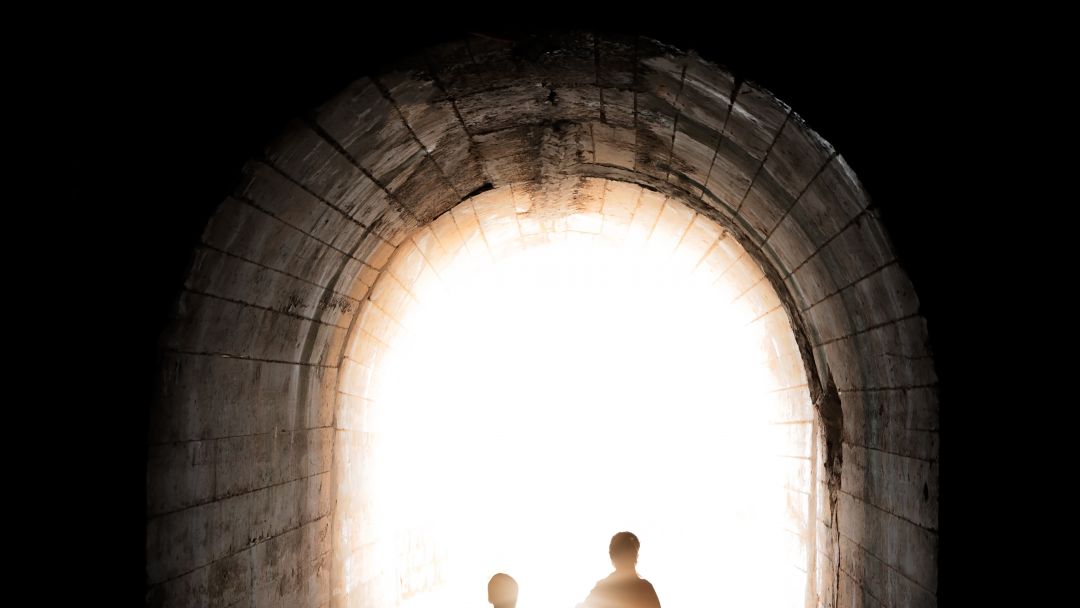

However, there is light in every darkness. For physical educationalists, it is coming in the form of unprecedented creativity in approaching the issue of online learning. Most schools have reflected on their hastily assembled attempts in the first lockdown, and produced programmes that have clearly captured the imagination of their pupils and inspired staggering levels of engagement.

Whatever the timescale, these conditions are temporary. There is reason to believe, and hope, that this lockdown might be the last one. So, the question remains as to whether this inventive work becomes redundant once schools return, never to be re-visited? Whilst the online delivery in virtual schools may not return, there may be lessons learned from this period of involuntary experimentation: conclusions that might inform school sport going forward.

What might these be?

Firstly, the level of voluntary engagement that schools have achieved in games sessions. Most have concluded that attempting to levy compulsion is unworkable, and therefore measured the success of their programme through levels of attendance. Rates up to 70% and beyond are amazing. Schools reaching these numbers appear to be offering both range and choice of activities. Traditional games practices and training continue to command the commitment of the keenest pupils, though they are happy to have regular sessions of other activities to leaven the diet. Other pupils have been happy try new experiences, and to establish a varied sporting experience. Maybe it turns out that it is not necessary for a pupil to have five sessions of Hockey every week, to the exclusion of all other sport?

Secondly, the enthusiasm of a great proportion of children for physical exercise. Possibly as a contrast to being confined at home, and hours of screen time, many pupils are voluntarily engaging with the wide range of fitness classes, activities and challenges that schools are establishing. Strava seems to have captured the imagination of many. Schools have reported surprise and delight at the levels of activity their pupils are willingly embracing. Perhaps it is the packaging that has contributing to the attractiveness of the fitness products, but it shows that being sedentary is not inevitable for teenagers.

Thirdly is the need for imagination. The regular school programme has continued, with only minor amendments, from year to year. The same handle is turned, and the same result achieved. When conditions made that impossible, and demanded new approaches and careful consideration of how best to achieve engagement and promote activity, the ideas turned out to be there all along. No advice was required beyond experimentation and unprecedented collaboration between schools in sharing conclusions.

At whatever stage schools return to relatively unrestricted activity, they will have a choice: do they consign the lockdown programme to a dusty file, and hope never to have to re-visit it? Or do they scour the conclusions for evidence of what might improve provision of sport and fitness in the medium term? Such evidence is not in short supply.